Home About us Contact us Protuner Loop Analyser & Tuner Educational PDFs Loop Signatures Case Histories

Michael Brown Control Engineering CC

Practical Process Control Training & Loop Optimisation

LOOP PROBLEM SIGNATURE PART 2-1

INTRODUCTION TO PART 2

AND PROCESS TRANSFER FUNCTIONS

Introduction to Part 2

The previous series of loop signature articles dealt with the basics of control loop optimisation, and concentrated on trouble shooting, and looked at “SWAG” tuning of simple processes. Apart from cascade control it only dealt with single input, single output loops in isolation from other possible interactive systems.

In this new series, consideration will be given to dealing practically with more difficult things like interactive processes, and with processes with much more complex dynamics.

In addition there will be more “tying up” of the practice to the theory. As a result you will get a much better understanding of the practice, and it will give you much more self-confidence in finding solutions to what can sometimes be difficult problems. Many delegates who have passed through our courses have reported back that the second Part has proved equally, if not even more valuable, than the first part, and in many instances they have managed to very successfully automate loops that previously had only run in manual.

Process Transfer Functions

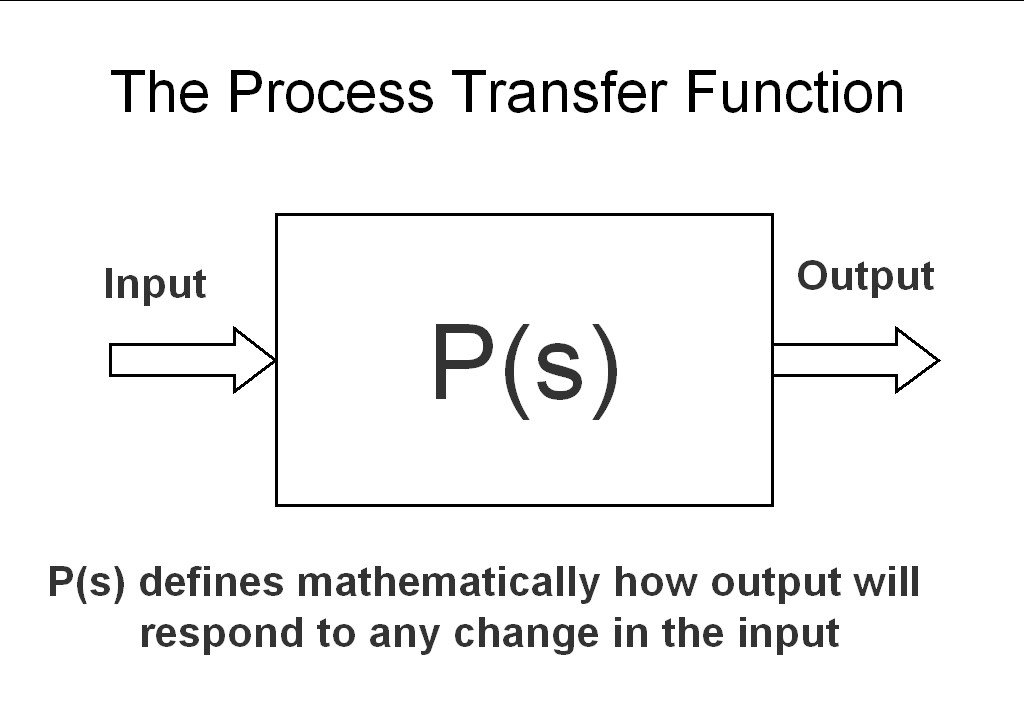

Figure 1

As shown in Figure 1 a process transfer function is merely a mathematical function describing how the output of a process will respond to any change on the input to that process. It is literally and simply a mathematical description of the process.

Now as mentioned in the Part 1 this function was considered by the mathematical control theory pioneers to be an absolute essential element which was needed in order to tune the controller. However unfortunately process transfer functions are relatively complex as both time and frequency responses are involved, and the best way of writing the functions is to use Laplace arithmetic.

Apart from the complexity of this for ordinary C&I people who mostly last touched on Laplace in distant studies at their educational institutions, it was historically found that it was extremely difficult, if not almost impossible, to actually practically establish the various dynamic Laplace constants of industrial processes by either frequency testing or from modelling them by making step changes on the process input. As a result most people forgot about all the theory they had learnt, and proceeded to “fly be the seats of their pants”, and as a result 98% of all optimisation was (and in fact generally still is) performed by WAG (Wild Ass Guess) or SWAG (Scientific Wild Ass Guess) methods.

Now as far as the author is concerned, in certain respects the need for process transfer functions is still as important today as it ever was. As will be seen the whole of this second series of Loop Signatures will be dealing with these functions. In many instances as will be seen, and provided the C&I practitioner has the right tools for the job, it will not be generally necessary for him or her to be too worried about very accurate values of the dynamic constants, and simplified transfer functions can in fact do a great job for certain tasks as will be seen a little later in the series.

However as also will be shown it is ABSOLUTELY VITAL when it comes to tuning, that the practitioner is aware of what constants are in fact present in the process response, and in some cases the relationship between the magnitudes of some of these constants is very important. Once you have established these things, one can then decide how best to apply different types of tuning to different types of dynamics, with sometimes startling improvements in control performance.

How can one establish the process transfer function dynamic constants in the modern world, when full frequency testing is not possible?

•Simple first order lag, deadtime models can be determined graphically as described in the first series. (Now before I get a flood of correspondence from people who would rightfully say that in the first series, I mentioned that these models are seldom good enough for good feedback tuning, please bear with me until later in the series where hopefully I will prove that although it is true for feedback tuning, some more advanced things like feedback compensators and decouplers are far less critical when it comes to tuning, and simple models generally are usually sufficient to tune them.)

•If you are fortunate enough to have access to a Protuner loop analysis software package, it gives simple first order lag, deadtime model on the tuning report, OR a much more complex model can be established from the relatively simple modeling procedures in the frequency plot section.

To summarise why it is necessary to have information of process transfer functions:

•As stressed above, a rough idea of the elements in the function should always be established when optimising any process

•Simple first order lag, deadtime models are needed for “SWAG” tuning methods, and are usually sufficient for tuning decouplers in feedforward and interactive control

•More complex models are often needed for off-line process simulation

In the next article in this second loop signature series we will be taking a look at an extremely powerful control tool, viz. feedforward, which in my opinion is not used nearly enough.